-9-

How Did A Nice Jewish Church Become Gentile?

Jesus, the founder of the Church, was a Jew. Not only was Jesus a Jew, but his disciples were all Jewish. They were all born as Jews and they lived as Jews. They worshipped regularly at the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem (Acts 2:46).

The early church was a Jewish church, with a Jewish constituency and Jewish leaders. Let us consider some evidences of these facts.

BACK WHEN CHRISTIANITY WAS ALL JEWISH

The miracle of the loaves and fishes is represented in this fifth

century mosaic at Tabgha by the Sea of Galilee

The earliest Jewish Christians were called Nazarenes (Acts 24:5). The biblical designation, Nazarene, is thought to have a connection to the word “Netzer” (branch) found in Isaiah 11:1. Later in the Talmud, Christians were called Notzrim. 1 The name Notzrim has persisted until the modern era, and is the name used to designate Christians in

Israel today.

We know from scripture that Jesus’ followers were first called “Christians” at Antioch during the New Testament era (Acts 11:26). After the first century there seems to have been a split in the group and we hear of some of these believers called Ebionites. Since this name means “the poor” it is thought that they were probably an ascetic group. They made their abode in the region east of the Jordan River.

This split may have been doctrinal in nature, and the Ebionites may have been the remnants of the earlier circumcision party. They upheld the whole of the Jewish law and vehemently rejected the letters of Paul. They apparently had a flawed view of the deity of Jesus. 2 The sect continued on for several centuries.

The Primacy of Peter Church is also located at Tabgha. This modern

structure is built over the ruins of a fourth century church.

The earliest Christians kept the Sabbath and Jewish festivals (Acts 13:13-15). Although the Apostle Paul was the disciple to the Gentiles, he was still thoroughly Jewish. He once hurried from Gentile lands to Jerusalem that he might arrive in time to keep the Jewish festival of Pentecost (Acts. 20:16). When he arrived in Jerusalem he underwent a Jewish ceremony of purification in the company of other Jews who had made vows to God (Acts 21:26). It is evident that the earliest Christians showed deep respect toward the requirements of the Jewish law (Acts 21:20).

The Church in Jerusalem continued as a Jewish Church for several generations. The Historian Eusebius reports that the first fifteen bishops of Jerusalem, until the time of Hadrian (AD 135), were all Hebrews. After the fifteenth bishop, Narcissus, we finally hear of Marcus, who is listed by Eusebius as being the first Gentile bishop of Jerusalem. 3 He also reports that the whole church consisted of Hebrews. 4

The foundation of the Capernaum synagogue probably goes back to the 1st century. Peter’s house was just a stone’s throw away, with Jews and Christians worshipping in close proximity.

(Photo credit Peggy Steffel)

The Jewish Church flourished in these early years. Lately, several artifacts have been uncovered to illustrate the presence of this Church. In Jerusalem early Christian sarcophagi have been discovered. On the Golan Heights, archaeological evidence of Christian\Jewish symbols has been found by French archaeologist, Dr.

Claudine Dauphin. 5

EARLY RELATIONS WITH GENTILES

The Church was so thoroughly Jewish from its earliest days that it greatly struggled with the problem of Gentiles. In Matthew 10:5-6, we see that this tension was also reflected in the ministry of Jesus and his disciples.

We see this problem regarding Gentiles continuing on for some time in the early Church. In Acts 8, we see the evangelist Philip going down to Samaria and proclaiming the Gospel. The Samaritans were a mixed people, the bulk of whom had been brought in by the Assyrians after the fall of the Northern Kingdom in 722 BC. These people believed Philip and many were converted by his preaching.

However, Philip’s revival in Samaria seems to have provoked a mini-crisis in Jerusalem. The Church immediately dispatched Peter and John to Samaria (Acts 8:14). Peter and John prayed and the new converts received the Holy Spirit. The situation then apparently became acceptable to the Church in Jerusalem.

Later, Peter had an experience with Gentiles, and this was in relation to the Gentile centurion, Cornelius (Acts 10:1- 11:18). The angel of God appeared to the devout Cornelius in Caesarea, and requested that he send for Peter. While Peter was in Joppa he himself had a vision, and in the vision God showed him many unclean animals and requested that he kill and eat of them. Although Peter was hungry, he still protested that he had never eaten of such non-kosher food. This vision of the unclean animals occurred to him three times. In the vision the Lord spoke to Peter that he should not call anything unclean that God had made clean (Acts. 10:15).

Just as Peter aroused from his vision, the emissaries of Cornelius knocked on the door. The Spirit instructed Peter that he was to go with them for they were sent by God. As he met the men, they told him about the supernatural events related to their coming. With all these preliminary preparations in mind it is surprising to see what Peter did later.

When he entered the house of Cornelius, he related how it was against Jewish law for him to be in the house of a Gentile (10:28). He then stated how God had shown him not to call anything unclean that God had cleansed. Then Peter asked the very strange question of Acts 10:29: “…May I ask why you sent for me?” It seemed that Peter, steeped in Judaism, was still unable to comprehend that Gentiles were about to come to the faith.

As Peter preached, the Holy Spirit then fell on Cornelius and everyone who heard. At this point, the Jews who had accompanied Peter were astonished that the Holy Spirit had come upon Gentiles (10:45). After this episode Peter went to Jerusalem. There the circumcised believers criticized him saying, “…You went into the house of uncircumcised men and ate with them” (Acts 11:3). Peter then had to relate his whole experience to the believers in Jerusalem. After they heard it, they all agreed that God had indeed granted repentance to the Gentiles.

Later, Paul was called by the Lord specifically as an apostle to the Gentiles (Rom. 11:13). He made much of his ministry and defended the presentation of the gospel to the Gentiles whenever it was threatened. On one early occasion Peter came to Antioch where Paul was. Peter freely ate with Gentiles until some men came from James and the Church in Jerusalem. Then Peter withdrew himself and would not eat with the Gentiles any longer. Seeing his example, other Jews including Barnabas also withdrew. At this, Paul arose and publicly rebuked Peter for his hypocrisy (Gal. 2:14).

Perhaps the greatest confrontation concerning the Gentiles happened at the Council of Jerusalem mentioned in Acts 15:1-35 and in Galatians 2:1-10. Paul’s ministry to the Gentiles had come under question and he, along with Barnabas and Titus, went up to Jerusalem to present his case before the leaders there. The question was whether or not Gentiles who believed would be required to become circumcised and keep all the requirements of the Law.

At this conference Peter was able to speak up on behalf of the Gentiles. After him, James, the leader of the Church, gave his opinion that the Church should not make it difficult for Gentiles coming to the faith (Acts 15:19). The question was resolved and it was determined that Gentiles would not have to become circumcised and keep the law. The leaders, James, Peter and John extended the right hand of fellowship to Paul and Barnabas.

We see that up until this time the Church in Jerusalem was very Jewish. This situation continued on throughout the first century and well into the second century. Gruber remarks about this saying, “In the first century, the most heated, controversial, doctrinal issue of all that the Church faced was: ‘How do the Gentiles fit into all this?’…Today the most heated, controversial, doctrinal issue that the Church faces is: ‘How do the Jews fit into all this?’” 6

GENTILE CHURCHES PATTERN AFTER JEWS

It is clear even in the early days of the Gentile church that it was closely connected to the Jewish Church in Jerusalem. Paul apparently patterned the Gentile churches after those in Judea (1 Thess. 2:14). He taught Gentile churches of their great debt to the people of Israel. He even insisted that because of this great debt, the Gentile churches should take an offering for believers in Israel (Rom. 15:27).

It is a surprising fact of church history that the first general offering mentioned in the New Testament is an offering taken among the Gentiles on behalf of Jews in Israel. It is also surprising that the bulk of stewardship teaching of the New Testament is based upon this offering for Israel.

Today the world-wide Church raises money for every conceivable program. Unfortunately, the modern Church seldom follows the biblical and blessed pattern of taking offerings

for Israel.

A FINAL PARTING OF THE WAY

Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. When this church was built by the Byzantines, Jews were forbidden to live in the city.

The decision of Jerusalem in Acts 15:5-29 concerning circumcision, undoubtedly helped to widen the growing rift between the Jews and Gentile Christians. Circumcision was, and is today, a critical matter for the Jews. However before AD 70, the Christians were still considered a sect of Judaism. We see this clearly in Acts 2:47, where the Church is described as “…enjoying the favor of all the people…” We see it again in Acts 24:5, where the “Nazarine sect” is mentioned.

The real problems began to develop somewhere around AD 66-70, with the Jewish revolt against Rome. At this time the Christians in Jerusalem fled to Pella in Perea. Pella was located in the present Jordanian foothills, about 60 miles (96.5 kilometers) northeast of Jerusalem. Later, Pella became an important center for Jewish Christianity. 7

The Christians probably fled Jerusalem because of the specific instructions of Jesus. In his prophetic utterance regarding Jerusalem’s destruction, he warned his followers to flee to the mountains when they saw the city being surrounded by armies (Luke 21:20-22). Although some from Jerusalem seem to have returned after the war, we can understand how Christians from this point on, must have been regarded as traitors to the

Jewish cause.

Not only was there a change in the Christian situation, there was also now a drastic change in the Jewish situation. In AD 70, Jerusalem was conquered and the Temple was destroyed by the Roman general Titus. The Jewish Temple, the sacrificial system, and numerous customs and practices of Judaism had come to an abrupt end.

However, during the siege of Jerusalem, a noted Rabbi by the name of Yohanan ben Zakkai escaped. With Roman permission he began a school at Yavneh (Jabne or Jamnia) near the Mediterranean coast. Rabbi Yohanan, a student of the famous Hillel, began a reformulation of Judaism along Pharasaic lines. The Sanhedrin was re-instituted. Some rituals of the Temple were transferred to the home.

His school began to stress acts of charity and kindness as a replacement for sacrifice. The reforms brought about by him and his school insured the survival of Judaism, even without a temple or a sacrificial system. Yohanan attempted to base Judaism upon the spiritual and not upon the territorial. 8

The reforms of the Yavneh school accomplished many constructive things. The Old Testament canon was defined there. Considerable work was carried on toward establishing the official text of the Hebrew Bible. However, Yavneh was also responsible for one other thing that made the division between Jew and Christian much deeper. Somewhere around AD 90, the Birkat ha-Minim (the Heretic Benediction) was adopted and made part of the Shemoneh Esreh (the Eighteen Benedictions), a prayer that is to be recited every day by devout Jews.

The Heretic Benediction, which was a condemnation of sects, may not have been drafted specifically against the Christians, but it certainly included them. 9 From this point on it would be exceedingly difficult for Jewish Christians to sit comfortably in the synagogue while their own faith was being cursed.

The final parting of the way was now close at hand. The stage was fully set with the Bar Kochba revolt against Rome in AD 132-135. Probably because Bar Kochba was looked upon as a messianic figure, and even acclaimed as such by the famous Rabbi Akiva, the Jewish Christians could not be involved. This war “was, for all essential purposes, the final major national blow that severed the two communities.” 10

After Rome’s second conquest of the Jews, the Emperor Hadrian renamed the city of Jerusalem Aelia Capitolina, after himself. On the Temple Mount he constructed a temple to Jupiter and forbade Jews to enter Jerusalem. Many of the surviving Jewish leaders went into hiding and eventually the Jewish center of learning was transferred to the Galilee. We can understand how contacts between Jews and Christians would become much more difficult after all this.

THE RIFT WIDENS

The Russian Church of Mary Magdalene on the Mount of Olives

We can clearly trace the events within Judaism that separated Jews and Christians. However, there were also events and movements within Christianity itself that contributed to the separation and even widened it.

As Christianity rapidly moved out into the Gentile world, it began to adapt itself to the Gentile culture. Its Hebrew roots were at first forgotten and later they were despised.

This trend is clearly seen in an early controversy over the proper dates of the Passover and Easter celebrations. In primitive times these were celebrated together.

Early in Church history when Anicetus was bishop of Rome (c. 155-166), he was visited by Polycarp Bishop of Smyrna. Although their visit was cordial, it was apparently arranged to settle a disagreement that had broken out over the proper date for Easter. Polycarp represented the eastern and more ancient tradition of having Easter in connection with the Passover, beginning on the 14th of Nisan. His position carried much weight since he had celebrated these festivals with John the disciple of the Lord. 11 Anicetus represented the Roman and western idea of choosing a separate date for Easter. He was apparently unconvinced by Polycarp’s arguments.

The Easter and Passover problem didn’t go away. It flared up again about 167 in Laodicea. There was difficulty again in 190, and several church synods were held to try and reconcile the problem. Eventually the decisions were in favor of the Roman practice. The eastern churches of Asia Minor, led by Bishop Polycrates of Ephesus, refused to accept the decision. At this the Roman bishop Victor excommunicated the recalcitrant

congregations. 12

When Christianity finally gained the ascendancy in the Roman Empire, the Passover problem was legislated from the Roman or Gentile position.

THEOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENTS

Even with the earliest church fathers, there was a tendency to deprecate the Jewish people and the biblical position of Israel. Wilson remarks, “By the time of Justin Martyr (ca. AD 160) a new attitude prevailed in the Church, evidenced by its appropriating the title ‘Israel’ for itself.” 13 Wilson carries this subtle theological trend to its conclusion

by saying:

A triumphalistic and arrogant Church, largely gentile in makeup, would now become more and more de-Judaized – severed from its Jewish roots. This de-Judaizing developed into a history of anti-Judaism, a travesty which has extended from the second century to the present day. 14

In the theological arena, there is probably no other person who has done so much damage to the Hebrew roots of Christianity as Origen (ca. 185-ca. 254), the early church father from Alexandria. Origen has been credited as being the father of the allegorical method of interpreting the scriptures. 15

This seems innocent enough at first glance. After all, there is such a thing as allegory in the word of God. In Galatians 4:21-31, Paul speaks of the allegory of the slave woman Hagar and her representation of the covenant of Sinai. It is contrasted with the Jerusalem above, which is free.

Unfortunately, Origen did not stop with these allegories of scripture. He insisted upon seeing almost all scripture in the allegorical sense. Much like some modern preachers, he could take an Old Testament text out of context and virtually preach whatever he wanted from it. For instance, when Origen saw “Israel” in the scripture, he knew it was a reference to the Church. 16

Gruber remarks, “It is Origen’s system of interpretation that produces the anti-Judaic ‘New Israel’ theology where the church replaces the Jews in the plan and purpose of God.” 17 “He lost no opportunity, in his sermons, to attack Jewish literalism, and his powerful invective no doubt made its contribution to the later tragic persecution of Jews

by Christians.” 18

St Anne’s Church was built by the Crusaders, who also murdered many of Jerusalem’s Jews

He looked upon anyone who did not accept his system as a “Jew,” and as someone who did not belong in the Church.19 When he spoke of “Jewish myths,” he was speaking of the Jews and their supposed literal interpretation of the Bible. He felt that “Jewish” and “literal” were virtually synonymous.20

It is sad when we consider that Origen had a great deal of interaction with the Jews and undoubtedly knew that the Jews did not always rely upon a literal interpretation. It was, in fact, the Hellenistic Jew, Philo of Alexandria, who had greatly influenced Origen with his allegorical interpretation.

Although Origen was considered a heretic in his lifetime and was later officially branded as such by the Church, his influence lived on and greatly increased.

Later, Pamphilus led the churches of Palestine to begin a theological school dedicated to promulgating Origen’s views throughout the whole Church. Pamphilus was the esteemed teacher of Eusebius, the church historian. Eusebius, in turn, devoted himself wholeheartedly to defending the views of Origen. Soon at the Council of Nicea, Eusebius helped ensure the triumph of Origen’s heresy. 21

THE COUNCIL OF NICEA

With the supposed conversion of the Roman Emperor Constantine, the nature of Christianity began to undergo a rapid and radical transformation. Constantine was eager to consolidate his gains and was determined to quell the various divisions within Christianity. Two problems were particularly difficult, the Arian Controversy, which contested the divine nature of Christ, and the continuing divisions over the proper date and celebrations of Easter. In the year 325, the Council of Nicea was called together by the new Emperor. Christian leaders, who a few short years before were persecuted and fed to lions, now traveled at state expense and with great fanfare to Nicea. The Emperor himself presided at the council. Eusebius, who was in favor with the Emperor, had great influence in the outcome of the discussions.

The Arian controversy was dealt with and also a conclusion was finally reached on the Easter celebration. The Church decided to accept the Roman custom of designating a separate day for Easter, quite apart from when the Passover would be celebrated by the Jews. We can understand the embarrassment of this now proud Gentile Church in having to consult the despised Jews on when to celebrate Easter.

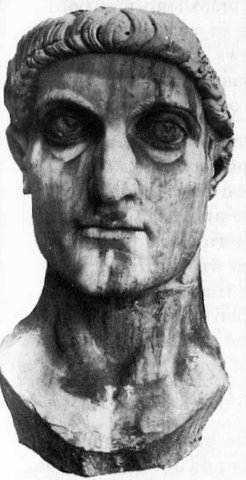

Constantine, the new “Christian” ruler of Rome

The anti-Semitic and anti-Hebraic flavor of this council can best be understood by taking a brief look at some of the statements in the letter of Emperor Constantine to the churches.

Here are a few of his statements:

…it seemed to every one a most unworthy thing that we should follow the custom of the Jews in the celebration of this most holy solemnity, who, polluted wretches! having stained their hands with a nefarious crime, are justly blinded in their minds. It is fit, therefore, that, rejecting the practice of this people, we should perpetuate to all future ages the celebration of this rite, in a more legitimate order….Let us then have nothing in common with the most hostile rabble of the Jews….In pursuing this course with a unanimous consent, let us withdraw ourselves…from that most odious fellowship. 22

The opinion of the Council was not to be taken lightly. Now the Church had behind it the full power of the Roman Empire. Any dissent would be looked upon as criminal. From this point on the sword of the Empire and not the sword of the Spirit would determine church doctrine and practice.

Gruber remarks that this council was a turning point in the history of the Church. He states that since this council, all Church theology has been built upon this anti-Judaic foundation. Israel was cast aside and the Church officially became the “new Israel.” 23 The teaching of contempt for Israel, along with haughty triumphalism would now be the norm – the only proper Christian attitude.

The early church historian, Eusebius, continued to make the rift wider between Christianity and Judaism. Eusebius in his writings promoted the heresy of Origen. In fact, Eusebius wrote a six volume defense of Origin in an attempt to convince the Church of Origen’s orthodoxy. 24

Eusebius believed that in Constantine, the fullness of the kingdom had come, and that the “new Israel” of the Church would now replace the old Israel. For instance, although there was much evidence in the primitive Church for belief in a literal millennium in Israel, Eusebius ignored the evidence and taught that the millennium was a carnal concept. This fit much better with his own views. He thought that this Jewish doctrine was unacceptable for Christians. 25

By his writings and influence, he did much to set the theological tone for coming generations. In fact, for the most part, the Greek fathers continuing through the third and fourth centuries would stand generally under the influence and spirit of Origen.26

THE CHURCH CUT OFF FROM ITS ROOTS

The Church of Constantine was now effectively cut off from its Jewish roots. It would receive its sustenance from the Greco-Roman and pagan culture around it. It could no longer be truly biblically-based. As Wilson points out, “It is impossible to be anti-Semitic or anti-Judaic and take the Bible seriously; otherwise one engages in a form of self-hatred.” 27

The trend would continue to modern times. The de-Judaizing of Christianity is clearly evident in some of our Bible translations. One may open the King James Version of the Bible and be astonished to see how clearly the Church has replaced Israel. As a general rule the Church is substituted for Israel in the headings at the top of the pages. Even in the beautiful passages speaking of the restoration of Israel in Isaiah 49, the heading reads, “Restoration of the Church.”

In its attempt to appropriate the heritage of Israel, the Church has been the real loser. In its bungled attempt, it has almost lost the heritage of Israel altogether. Today the modern Church tries to draw its life from every possible source, yet it withers; it fades; it starves for true nourishment.

STUDY QUESTIONS:

What are some evidences that the earliest Christians followed Jewish practices?

Were Gentile believers readily accepted into the earliest Christian assemblies? Give a scripture to back up your answer.

Name three events that may have contributed to the final separation of Judaism and Christianity.

What were some positive achievements of the Yavneh (Jabne) school?

How did the choosing of the date for Easter help separate the Christian church from its Hebrew roots?

How did the allegorical method of interpreting scripture aid in the growing Christian anti-Semitism?

In what way was the Council of Nicea a watershed in the Church’s relation with Israel?

NOTES

1. Marvin Wilson, Our Father Abraham, Jewish Roots of the Christian Faith (Grand Rapids, MI and Dayton, Ohio: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Grand Rapids, MI and Center for Judaic-Christian Studies, 1989) p. 41.

2. Michael Walsh, Roots of Christianity (London: Grafton Books, 1986) p. 101.

3. Isaac Boyle, trans. The Ecclesiastical History of Eusebius Pamphilus (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Book House, eighth printing 1976), p. 192.

4. Isaac Boyle, trans. The Ecclesiastical History of Eusebius Pamphilus, p. 130.

5. See Dispatch From Jerusalem, July/Aug. 1994 Vol. 19. No. 4, p. 1.

6. Daniel Gruber, The Church and the Jews, The Biblical Relationship (Springfield, MO: General Council of the Assemblies of God, Intercultural Ministries, 1991) p. 2.

7. Wilson, Our Father Abraham, Jewish Roots of the Christian Faith, p. 76.

8. Wilson, Our Father Abraham, Jewish Roots of the Christian Faith, p. 77.

9. Wilson, Our Father Abraham, Jewish Roots of the Christian Faith, p. 69.

10. Wilson, Our Father Abraham, Jewish Roots of the Christian Faith, p. 81.

11. Philip Schaff, History of the Christian Church, Vol 2, Anti-Nicene Christianity (Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, MI, 1910) p. 213.

12. Williston Walker, A History of the Christian Church (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1959) p. 62.

13. Wilson, Our Father Abraham, Jewish Roots of the Christian Faith, p. 83.

14. Wilson, Our Father Abraham, Jewish Roots of the Christian Faith, p. 84.

15. Gruber, The Church and the Jews, The Biblical Relationship, p. 11.

16. Gruber, The Church and the Jews, The Biblical Relationship, p. 11.

17. Gruber, The Church and the Jews, The Biblical Relationship, p. 12.

18. Nicholas DeLange, Origen and the Jews, Studies in Jewish-Christian Relations in Third -century Palestine (London-New York -Melbourne, Cambridge University Press, 1976) p. 135.

19. Gruber, The Church and the Jews, The Biblical Relationship, p. 15.

20. DeLange, Origen and the Jews, Studies in Jewish-Christian Relations in Third -century Palestine, pp. 105-106.

21. Gruber, The Church and the Jews, The Biblical Relationship, p. 17.

22. Quoted in, Gruber, The Church and the Jews, The Biblical Relationship, p. 30.

23. Gruber, The Church and the Jews, The Biblical Relationship, p. 1.

24. Gruber, The Church and the Jews, The Biblical Relationship, p. 9.

25. Gruber, The Church and the Jews, The Biblical Relationship, p. 18.

26. Gruber, The Church and the Jews, The Biblical Relationship, p. 12.

27. Wilson, Our Father Abraham, Jewish Roots of the Christian Faith, p. 20.